*For those people who find images of carved fish heads and bodies disturbing, please note that such images occur within this post.

Almost every account aimed at educating tourists about the famed Tsukiji fish market in Tokyo will tell you that the key to a successful visit involves waking up well before the sun rises. The fish and seafood actually start arriving from all over the world before the previous day has ended, and by 5 am the wheeling and dealing is in full swing. This is what most people come to Tsukiji to experience: a glimpse into the nexus of a multi-billion dollar industry unlike any other.

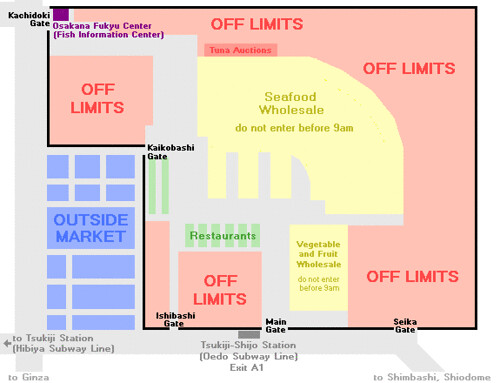

Many of the write-ups, however, also mention how a 2008 incident involving a tourist allegedly licking a tuna head has made what were already wary employees even more disdainful of the unanticipated and unwritten addition of "tourist attraction" to their business cards. As the always considerate, always respectful traveler, and appropriately scared off by warnings that the people who do the real business in Tsukiji hate bumbling tourists getting in their way and taking pictures willy-nilly, I early on decide not to attempt to navigate the wholesale auction aspect of this behemoth. Instead, I reason that I can save the early morning taxi fare (new procedures have tourists lining up hours before the subway trains start running), abstain from participating in the depletion of the world’s stock of tuna, and still soak in the atmosphere of the more tourist-friendly outer market.

After a few delays thanks to the snooze button, I finally drag myself out of bed, hating, as usual, the feeling of having to wake up while it is still dark outside. In this part of the world, however, the sun rises early, and despite the cloaked-in, wee hours of the morning feeling of my hotel room, I draw open the curtains to see that it is full daylight outside.

Or perhaps I simply don’t get up at 6 am enough to realize that this is the norm in the summer, regardless of geographical location.

When I arrive at Tsukiji, I’m immediately thrown for a loop. Thinking that I had missed the height of the wholesale chaos, I nonetheless encounter an endless stream of trucks, mechanized trolleys aka "turret trucks", and scooters that seem destined to mow me down at some point. I can hardly figure out where one is supposed to go, and blindly walk in what seems to be the direction of the center of activity.

As I try to make sense of my surroundings, I find myself in the outer market area where auxiliary businesses support the main business of the fish traders: stalls selling all manner of knives, tubs of assorted pickled vegetables, bins upon bins of bonito flakes, ceramicware ranging from the intricately detailed to straightforwardly functional, thick logs of tamago (egg cakes), and, of course, a host of sushi purveyors. I weave through the pathways of this more familiar, consumer rather than wholesale setting, and begin to feel calmer, less overwhelmed, and more able to keep my wits about me.

By the time I have explored every nook and cranny of the outer market and filled my belly with a sushi breakfast, I feel reasonably satisfied with my visit, notwithstanding the fact that I have yet to actually see where the real business of Tsukiji takes place. As I walk around considering where to go next, however, I see some tourist-looking people headed towards a large building. In one of the few instances of finding comfort in the presence of other tourists in the context of traveling abroad (as opposed to that, "Oh, man, you're here too?" feeling), I reason that they must know where they are going, and that there is some shielding from the wrath of angry fishmongers to be found in sticking with other tourists. So I take advantage of a momentary lapse in the steady stream of traffic that still surrounds the market, and with the help of TWO crossing guards, finally find myself in the main seafood market.

There's a definite buzz going on, but as I pick my way through puddles and dodge temporary styrofoam aquariums, I come to realize that I have inserted myself into something less than a full-fledged business trading floor. I also learn that if you want to fit in to this place, the key is to invest in some rubber boots.

At around 9:30 in the morning, the height of the activity has long since diminished, but there are still a few hours to go before the market fully shuts down for its daily top-to-bottom cleaning, replete sprinkler trucks. Though the main attraction of Tsukiji is the bluefin tuna auction drawing buyers and sellers from around the world (though most of the fish ends up in regional restaurants), I find a certain magic in this winding down time, in limbo between the real business of the day and the full-shutdown of the market. The wholesalers are standing around, or visiting each other’s stands, and I feel like I am granted a glimpse into the underlying camaraderie that must maintain the social networks of this place above and beyond the wheeling and dealing. A gray-haired gentleman leans in closely as a younger protege slices through a massive hunk of deep red tuna with careful deliberation. Others walk a U-shaped pattern, coming down the narrow walkway between the freezers and trays in front of their stall, briefly joining the public path, then turning to walk up to another stall to greet their friends, competitors, and colleagues with a handshake and perhaps a word on how their accounts went in the hours prior. There is still some business to be had, tourists or other regular consumers taking their bounty away in bags rather than crates or order slips, but for the most part, this seems to be a window of time dedicated more to socializing than to transactions. Not only do I feel distinctly outside of these exclusive social circles, I am also acutely aware of my status as one of the few females in what is clearly a male-dominated industry. Rather than globalized trade routes or international commodities, I think of sociology studies, of the inherent fraternal nature of this place and the business it supports.

Interestingly, this fraternal socialization thrives even amongst the vaguely abattoir setting of a wholesale fresh (and freshly killed) seafood warehouse. There is good reason for the ubiquitous rubber footwear worn by those in the know: against the dark floor, it is difficult to discern spilt water from spilt fish blood. While I am an unabashed omnivore, and reasonably accustomed to confronting the realities of living at the top of the food chain, I find the constant reminders of death intriguing, a candid mix of mortality, the moribund, and the morbid all together. A few styrofoam containers appear stained with a deep garnet hue, while others hold more explicit deep sea entrails. Turret trucks neatly cart off open tubs of fish carcasses, while mounds of fish heads patiently await their due processing on the ground.

I come across a lone fish cutter, hacking away at a giant head. The presence of a few other tourists gathered around him makes me think that taking a picture would be okay, and with my flash turned off, I quickly do so.

Then another man comes up to the fish cutter, says something in Japanese, and they both glance in my direction. "Shit," I think, "so much for being the considerate and respectful traveler." The fish cutter gives a shrug, though, and continues about his business. I've been let off the proverbial hook, it seems, though I wouldn't be surprised if I was unwittingly the subject of some bad words in Japanese.

Though I still would not recommend this place for the squeamish, there is actually a greater sense of sanitization amongst the refuse here than in some of the wet markets that I've walked through in Hong Kong. Perhaps this comes from my knowing that the market completely shuts down every day for the sole purpose of cleaning. Or maybe it is just that, unlike those markets that I visit during regular business hours, here I am seeing people in the active business of cleaning up following a day of work, methodically soaping up and hosing down their stations. I was struck in particular with one stall that had long since packed up for the day. At the very front of the stall, carefully laid out on a wooden chopping block were, literally, the tools of trade. All sorts of knives of varying lengths and sizes, lined up with such precision one might think that Her Majesty the Queen's butlers had stopped by with their rulers. Taken by the latent sense of non-ostentatious pride in the display, this time I seek permission before taking out my camera. Mobilizing my limited Japanese language skills, I tentatively call out to the man smoking at the back of the stall.

"Sumimasen?" I mime taking a picture of the knives.

He doesn't respond at first, and I think, "Shit, I'm that horrible tourist they hate." But then he nods, and without a word or a smile, flicks on the lamps that hang directly over my subject before leaving me to my business. I quickly snap a few photos, and then, having already used up most of my Japanese skills, draw upon the dregs of my vocabulary. "Domoarigato," I say as I do a sort of odd, uncertain bow, which seems both appropriate and totally out of place at the same time. He just nods, cool as a cucumber, and descends to re-extinguish the lamps.

I finally leave the place in awe of some of the amazing things I’ve seen. But I also leave with a conflicted sense of this place’s status as a “must-see” tourist destination in Tokyo. In tourism studies speak, the Tsukiji fish market presents a blurring of the front- and back-stage areas of tourism performance. The massive scale of trade that goes on in this place has made it an international tourist destination. And yet, what makes this place more touristic or less a workplace than any other wholesale distribution warehouse on the outskirts of a major city? What makes these fish tradesmen more “performers” than their lesser photographed and visited counterparts on the docks of New York or outskirts of Paris?

A wholesale food distribution warehouse is right up my alley as an interesting diversion, a distinctive experience, and an opportunity to better understand our food supply chain. But I also sympathize with those Tsukiji employees who find the due course of their business impinged on by people looking for something new and novel, people who see a place of work as a playground for leisure, rather than as a livelihood. Perhaps, though, this all reflects the general theme of globalization that underlies modern tourism and trade. Just as globalization renders geo-political borders subservient to commerce and money, the barriers between everyday life, tourism, and performance get blurred as well.